19 Reconstruction III: End of Reconstruction

The End of Reconstruction

Jim Ross-Nazzal

Even Republicans lost interest in Reconstruction, in part because General Grant’s presidency was generally a failure due to the numerous political scandals, which eventually led to Democrats taking back control of Congress. Once Democrats regained power of the purse strings, Congress would no longer pay to defend the black southerners against what Grant called the “annual autumnal raids” (the Klan). Grant was not personally involved in the various schemes and scandals his friends and relatives were engaged in. Republican interest in Reconstruction began to be replaced with other objectives as more liberal Republicans and Democrats won public office. In 1873, the Cooke banking industry collapsed (the major bank for the North during the Civil War) which caused a national depression. The depression will last for many years. Some argue two decades. But there were specific reasons why Reconstruction came to an end and those had to do with violence, corruption, race, factionalism and the election of 1876.

Violence

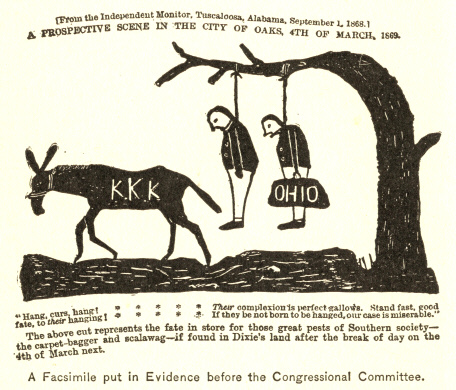

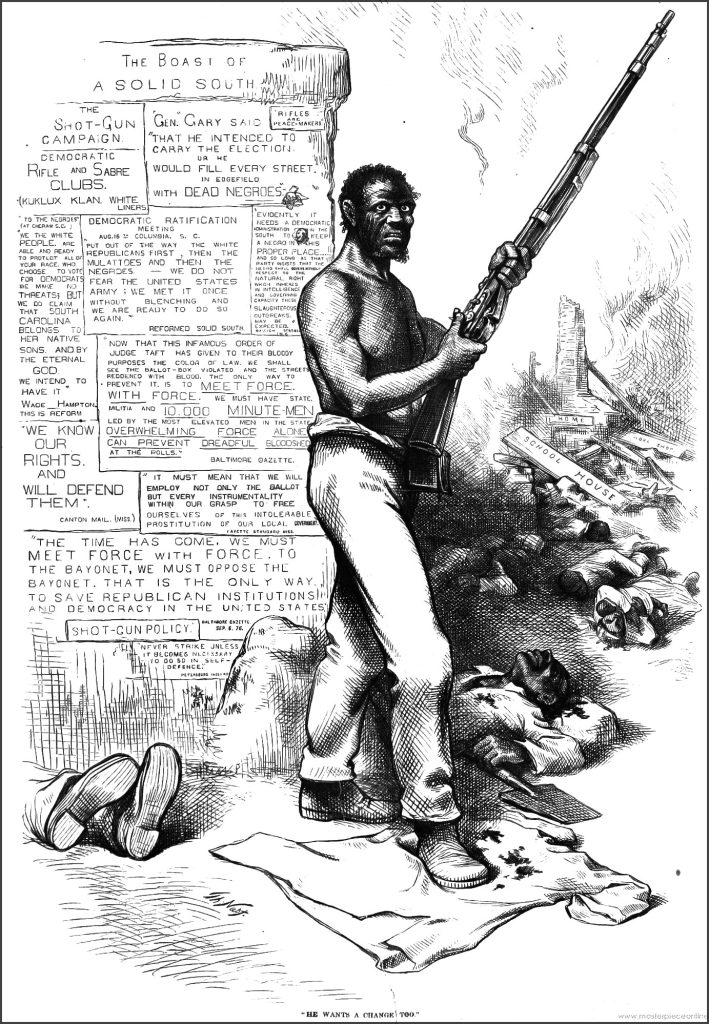

The KKK was a particularly effective political-terrorist organization. Their leaders conducted a systematic campaign to reduce the Republican vote by focusing on counties in which the black and white populations were relatively equal. Most of the time the attacks happened before elections in order to kill and/or scare off enough black men (who were suspected Republican voters) to tip the scales in favor of the Democrat candidate, believing that white men would vote Democrat. Congress passed the 1870 and 1871 Klan Acts (states and individuals could not discriminate) and appropriated money so that the Army could put down what President Grant called those “annual autumnal raids.” But after 1872, there was no serious federal intervention to deal with the violence in the South. And by 1874 all federal intervention disappeared. 1874 was a non-presidential election year. Democrats won control of the House of Representatives. So even if Grant wanted to go after the KKK, the House would not appropriate the money necessary to support the operations.

By the late 1870s, Northerners were also getting tired of the endemic violence, with periods of epidemic violence, in the South. That was not the sentient in 1865 when the Chicago Tribune declared “The men of the North will convert the State of Mississippi into a frog-pond before they will allow any such laws to disgrace one foot of soil in which the bones of our soldiers sleep and over which the flag of freedom waves.”[1]

Corruption

There was so much corruption in Republican southern governments, the Freedmen’s Bureau as well as the Grant administration to the advantage of the Democrats who portrayed the southern governments as inherently corrupt and not fixable. Such as in South Carolina:

“Corruption flourished in the state legislature and in the executive offices of the state. In one instance in 1870–1871, the state’s financial board secured the authority to print and sell $1 million in state bonds; there were to be $1,000 bonds numbered 1 to 1,000. Members of the board printed two sets— both numbered 1 to 1,000—and sold both sets. They kept no records of their transactions and were caught only when a New York investment firm came into possession of two bonds with the same number on both. Partly as a result of such malfeasance, and partly because of legitimate increases in expenditures such as the creation of a public school system from scratch, state budgets skyrocketed during Reconstruction and the state slipped further and further into debt.”[2]

In Louisiana, charges of corruption and periods of violence went hand in hand:

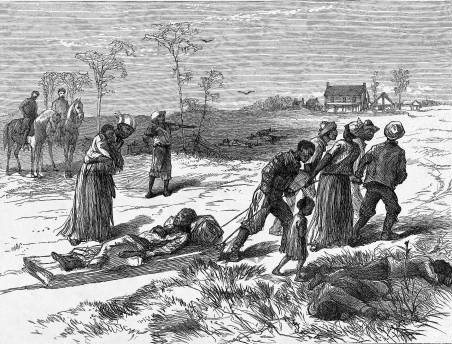

“The Colfax Riot was the bloodiest single instance of racial violence in the Reconstruction era in all of the United States. Disputes over the 1872 election results had produced dual governments at all levels of politics in Louisiana. Fearful that local Democrats would seize power, former slaves under the command of black Civil War veterans and militia officers took over Colfax, the seat of Grant Parish, and a massacre ensued, including the slaughter of about fifty African Americans who had laid down their arms and surrendered. . . . White League influence spread to northwest Louisiana in the summer of 1873. Its brutal actions targeted whites as well as blacks. One such episode was directed against the family of carpetbagger politician Marshall Harvey Twitchell. In 1874 the White League, who arrested and executed Twitchell’s brother, two brothers-in-law, and three other white Republicans, while Twitchell was in New Orleans. Twitchell returned to Coushatta from New Orleans with two companies of federal troops, his goal to restore Republican rule in the parish. Democratic leaders continued to control local politics, however. In 1876 they assassinated Twitchell’s brother-in-law, and tried to kill Twitchell, who lost both arms in the fray.”[3]

Northerners were aware of the corruption of Republican governments and institutions in the South and southerners pleaded for sympathy. At that time, northerners were dealing with Democrat corruption -Tammany Hall, which also turned its attention to assisting immigrants. Which brings us to the racial issue.

Race

Rutherford B. Hayes was a staunch abolitionist. As president, Hayes defeated the Democrats’ attempt to repeal election laws that would have undermined the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments. After leaving office, Hayes became involved in civil and social rights’ conferences for Native Americans and African Americans at Mohonk Lake House in upstate New York. Most Americans did not think like President Hayes. Most Americans were not dedicated to racial equality. In fact, Radical Republicans might have been more focused on punishing the South than on helping the freedmen in their transition from slavery to freedom.

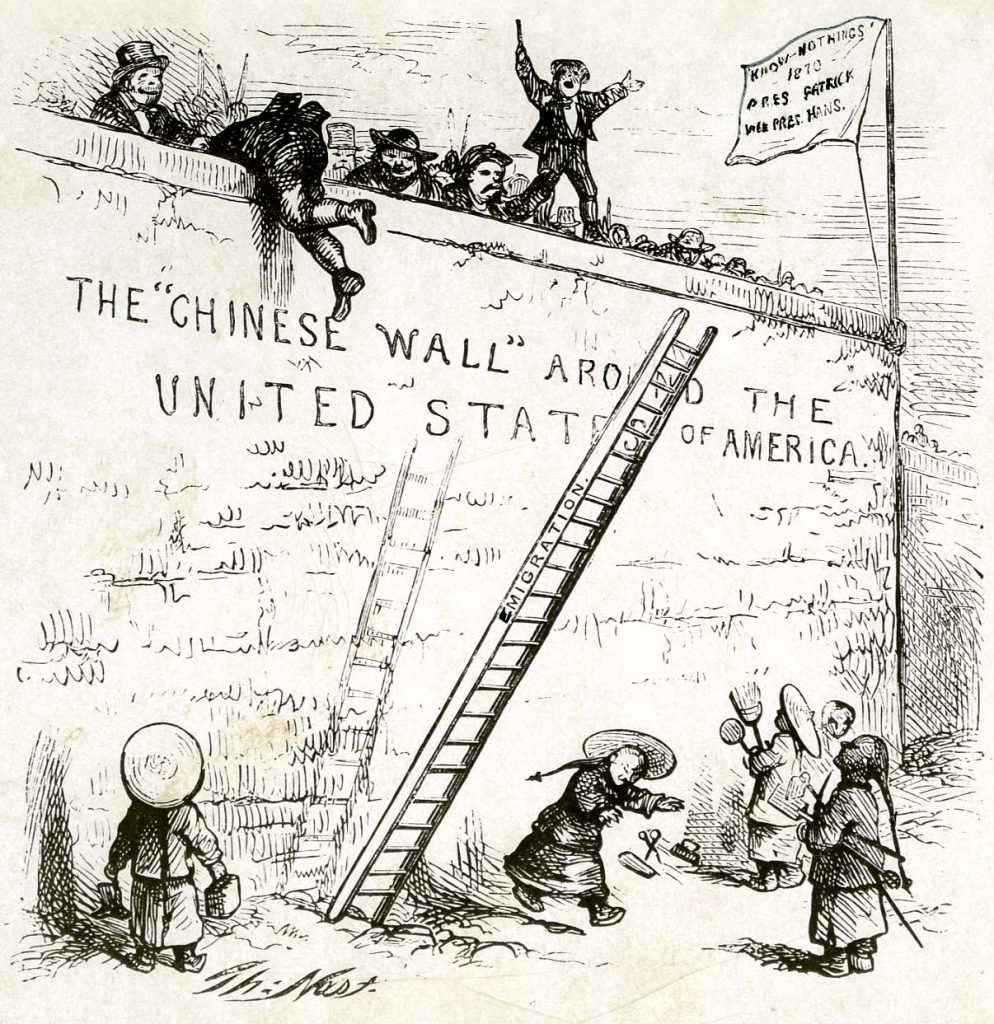

Late in Reconstruction was the beginning of massive waves upon waves of immigrants from southern, central, and eastern Europe. From places that did not have a history of democracy or capitalism. Those new immigrants did not come to the US already speaking English. In fact many believed themselves to be transients: make some money then go home. However, those stories of American roads being paved in gold were false and once they got here they quickly realized they were here to stay. So many non-English speaking people with no knowledge of democracy or capitalism entered the US through northern ports that white southerners could argue that while the North had their Russian Jews and Polish Catholics, the South had blacks and thus they (white northerners and southerners) shared a common Anglo-Saxon heritage, culture, and history. This was a period of Social Darwinism (see the chapter on Social Darwinism and US Foreign Policy).

Factionalism

Republicans could not get on the same page. The largest Republican block in the South was Black, but they held fewer positions than Whites. Black Republicans wanted more social programs or social reform from education to protection from the KKK. Scalawags sought such things as farming assistance and to disenfranchise ex-Confederates. Carpetbaggers wanted money for infrastructure, especially railroads and ports. Republicans factionalized the South. While Democrats in the South were united in the goal of ousting the occupying forces and Democrats in the North wondered how long the occupation was going to last?

Over time those corrupt southern Republican governments lost legitimacy in the minds of northerners. Besides the new mentality is that you can’t keep fighting forever and they grow tired of trying to turn the South into that frog pond. The idea of righteous indignation of the 1860’s was gone. Resolve was waning in the North. New issues rose pertaining to the economy and political conditions such as the 1873 Depression and the Tompkins Square Riot of the following year. In both cases class and violence went together. In the former there were strikes, layoffs, great division between capitol and labor and tremendous violence when owners (backed by government -usually governors) tried to put down strikes, usually ending in the deaths of the strikers. Coal mine owners and governments worked to put down strikes in Kentucky and West Virginia through the 1920s. Those violent tactics did not become illegal until 1933 (see the chapter on FDR and the New Deal).

Although Grant won reelection handily, corruption in his administration was endemic. Some saw similarities between corruption in the top Republican government in DC and in those smaller Republican governments throughout the ex-Confederacy. More and more Republicans even wanted to return to “home rule” for the South, they sought civil service reform, break up the Tweed Ring, and to deal with the numerous northern domestic issues. Just cut the South loose to deal with their own problems.

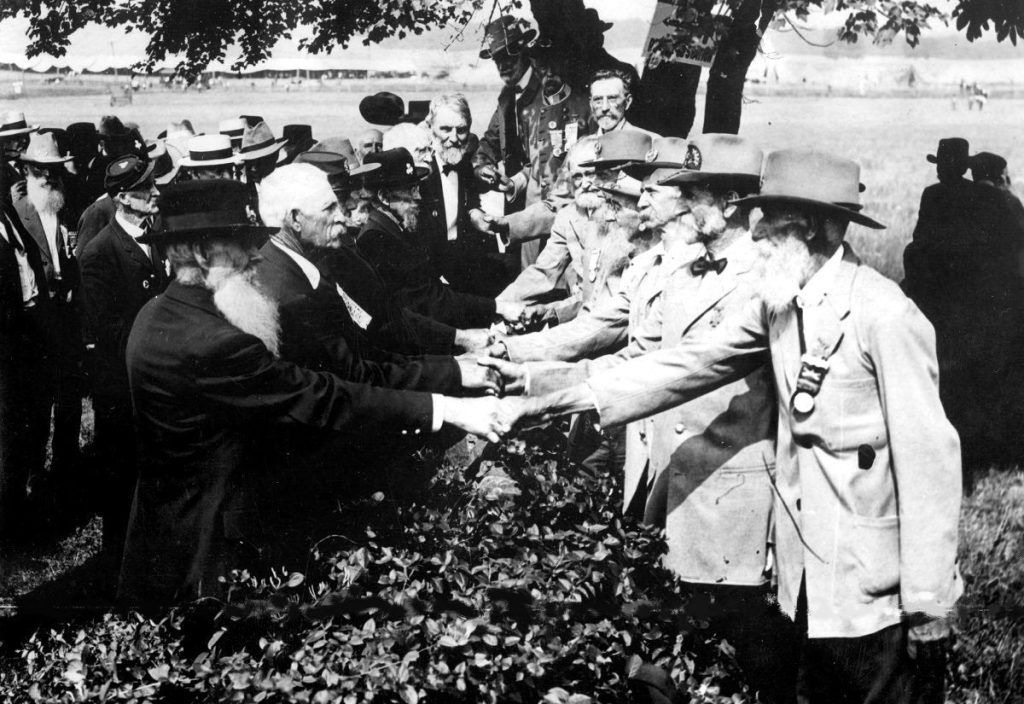

And then in 1875 Union and Confederate veterans decide to hold their annual conventions together. For the first time these once-enemies met again. And as we all do when we get older, those veterans romanticized their past. They were braver. Their feats more Sampsonian. But they talked about their children or grandchildren. They swapped buttons, caps, or other souvenirs. They took pictures with one another Topics such as slavery or states’ rights were out of bounds. Let bygones be bygones seems to have been the theme of that 1875 meeting. Both at the veterans’ meeting as well as throughout American society, by 1875 the socio-economic-political element which was the underpinning of the war -slavery- began to leave Americans’ collective memory. The national railroad strike of 1877 really drew everyone’s attention away from Reconstruction. But the final straw in the back of the camel which is Reconstruction was the 1876 presidential election.

1876 was a presidential election year and the centennial celebration of this country’s founding. Celebrations took place all over the US but the largest celebration, in the form of an international fair or festival, took place in Philadelphia. One of the exhibits was the first piece of what would become a massive statue. A gift from our first ally of the American War for Independence -France. They gave the US the Colossus:

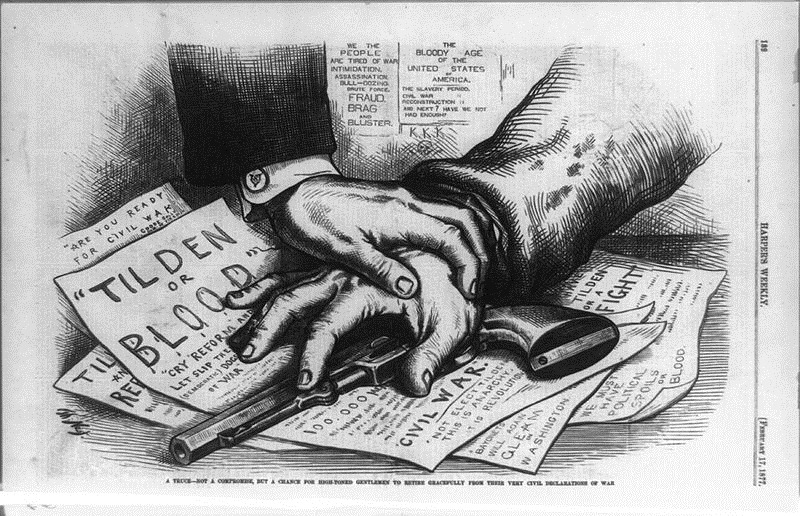

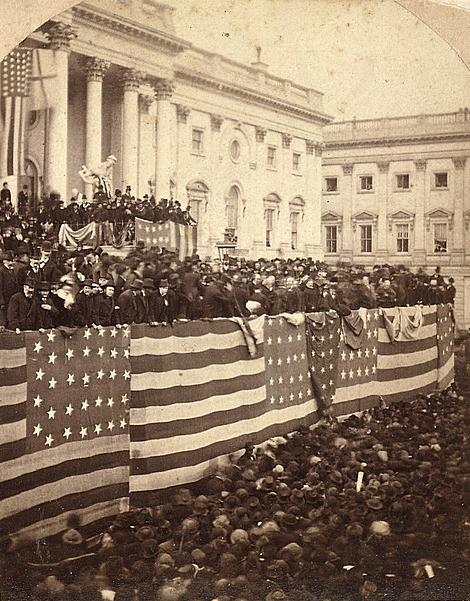

Americans wondered, “How long are we going to fight the Civil War?” Samuel Tildon, the Democrat from New York ran on the idea that Reconstruction was over. If elected, he would remove all Union troops from the South and push Congress to appropriate funds for infrastructure improvements. The Republican, another Union general, Rutherford B. Hayes, from Ohio, argued that Reconstruction had not ended. Although Tildon won the popular vote, he was one vote shy of winning the Electoral College due to numerous inconsistencies of vote counting in states such as Florida. Hayes, who lost the general election, needed all of Florida’s electoral votes to become president. There were also issues in Louisiana and Oregon.

Congress created a special committee consisting of 15 members: five Representatives, five Senators, and five from the Supreme Court. Seven Democrats, seven Republicans, and one Independent. The one Independent came from the Supreme Court. His name was David Davis. The Independent stopped down before casting his vote and was replaced by a Republican from the Supreme Court (there were only Republicans remaining) so with eight Republicans and seven Democrats, they voted along party lines: 8 in favor of giving the electoral votes to Hayes and 7 in favor of giving the electoral votes to Tildon, thus by one vote Hayes became the next president.

Hayes was not the first person to lose the popular vote but become president. That honor went to Andrew Jackson in 1824 when John Quincy Adams, who lost the poplar vote, became president. And there will be others. For example, in 2000 Al Gore (D) won the poplar vote but there were irregularities with the vote count in Florida. The loser of the poplar vote, George W. Bush (R) sued to stop the recount. The case went before the Supreme Court. 8 justices were appointed by Republican presidents and 7 by Democrats. And that’s how they voted, along party lines to give Florida’s electoral votes to the loser of the poplar vote. Thus, by one vote of a Supreme Court justice the will of the American people was ignored in 1876 and in 2000.

Democrats would not contest the election if they got several things to include:

- Pull military out of the South

- Build a railroad in the South

- Build flood control improvements along the Mississippi River

- Widen and deepen major ports in the South

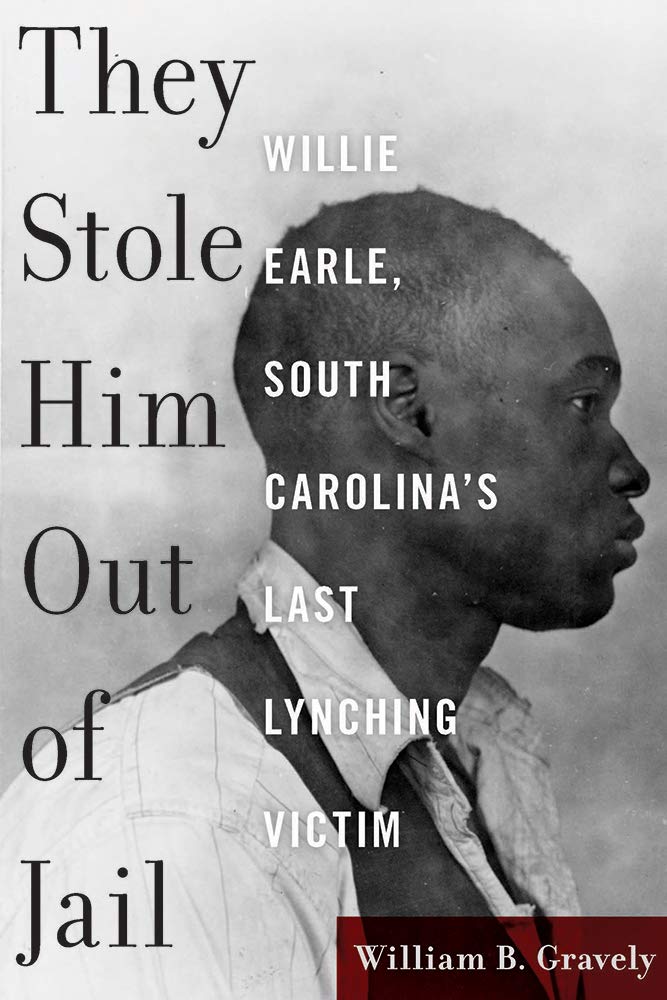

Republicans agreed. The Redeemers (such as Wade Hampton, governor of South Carolina) promised to treat their black populations well, Hayes recognized the Redeemer governments, and Blacks are on their own for the next 100 years. Hampton (the “Savior of South Carolina”) was an ex-Confederate general, one of the largest slaveholders in US history and used violence to squash black voters with the help of the Red Shirts -a paramilitary terrorist organization. He would not fulfill his promise of equality among his citizens. Lynchings were the hallmark of racial violence and terror. Lynchings in South Carolina would last another 70 years.

So, was Reconstruction a success? That depends on how you define “success” as well as when you define that success happening. The Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments to the Constitution are huge. Those three alone demonstrated a massive shift in every aspect of American society. Citizenship. Equal protection under the law. They provided for political gains such as voting and office holding. There were social services such as education from those small Freeman’s Bureau schools to what became major universities such as Southern, Fisk, and Howard. 3.5 million people were free to make their own decisions. To live their own lives as they saw fit.

Some of Reconstruction’s shortcomings includes the economic aspects -there was no lasting efforts to redistribute the economic pie and probably wrong to believe a redistribution of wealth would ever take place considering Americans’ views on laissez-faire capitalism at that time. Political gains such as office holdings were short lived. In fact, you could use the phrase “there should have been . . . ” to examine all of the problems with Reconstruction.

While slavery came to an end (Thirteenth Amendment), those born in the US became citizens with the equal protect clause (Fourteenth Amendment), plus universal male suffrage (Fifteenth Amendment), those changes to the Constitution existed on paper. It’s easy to change laws. It takes a long time, if at all (“very fine people on both sides”) to change minds and hearts. Black Codes. Redeemers. Lynchings. Segregation by law. Separate but equal. Did nothing meaningful change until the federal government stepped back into the fray in 1964 with the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, followed by the Voting Rights Act of 1965?

Reconstruction will eventually succeed, but not in 1877. In 1877 the average ex-slave was illiterate, was broke, and got chased around by guys in sheets. However, there were identifiable human beings by then. During slavery, it was not unusual for slaves to be recognized as sex and age, maybe ability as well. As in “Male, around 20, field hand” or “Female, 11, seamstress.” But by Reconstruction ex-slaves became identifiable human beings with thus could you argue that Reconstruction was a success by 1877, going from a slave to an individual person with rights (even if those rights are only on paper)? Too philosophical for this historian. Reconstruction was a failure by 1877 is the low-hanging fruit.

By the way, in 2013 the US Supreme Court began dismantling parts of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. States, such as Texas, acted almost immediately to change their laws. The result was lowered voting rates among African Americans. Some alleged voter suppression. So, by 2015 were the Reconstruction-era Republican ideas of political equality and political success (the Fifteenth Amendment and its predecessor, the Voting Rights Act) being chipped away? Let’s take a look at that in the second part of this OER.

As with the other chapters, I have no doubt that this chapter contains inaccuracies, therefore, please point them out to me so that I may make this chapter better. Also, I am looking for contributors so if you are interested in adding anything at all, please contact me at james.rossnazzal@hccs.edu.

- "Southern Legislation in Respect to Freedmen," by J.G. de Roulhac Hamilton, in Studies in Southern History and Politics, p. 138 ↵

- http://www.scencyclopedia.org/sce/entries/reconstruction/ ↵

- https://www.crt.state.la.us/louisiana-state-museum/online-exhibits/the-cabildo/reconstruction-a-state-divided/index ↵